Reimagining public washrooms: Inside the winning design

Alea Reid and Petra Matar, intern architect and architect principal at Design Partners in Architecture and Interiors (DPAI), a Hamilton-based architecture, interiors, and urban design firm, spoke to Tanya Martins, online editor at Construction Canada, about their winning design for TO the Loo!, a global design competition to imagine the future of public washrooms in Toronto.

Design process

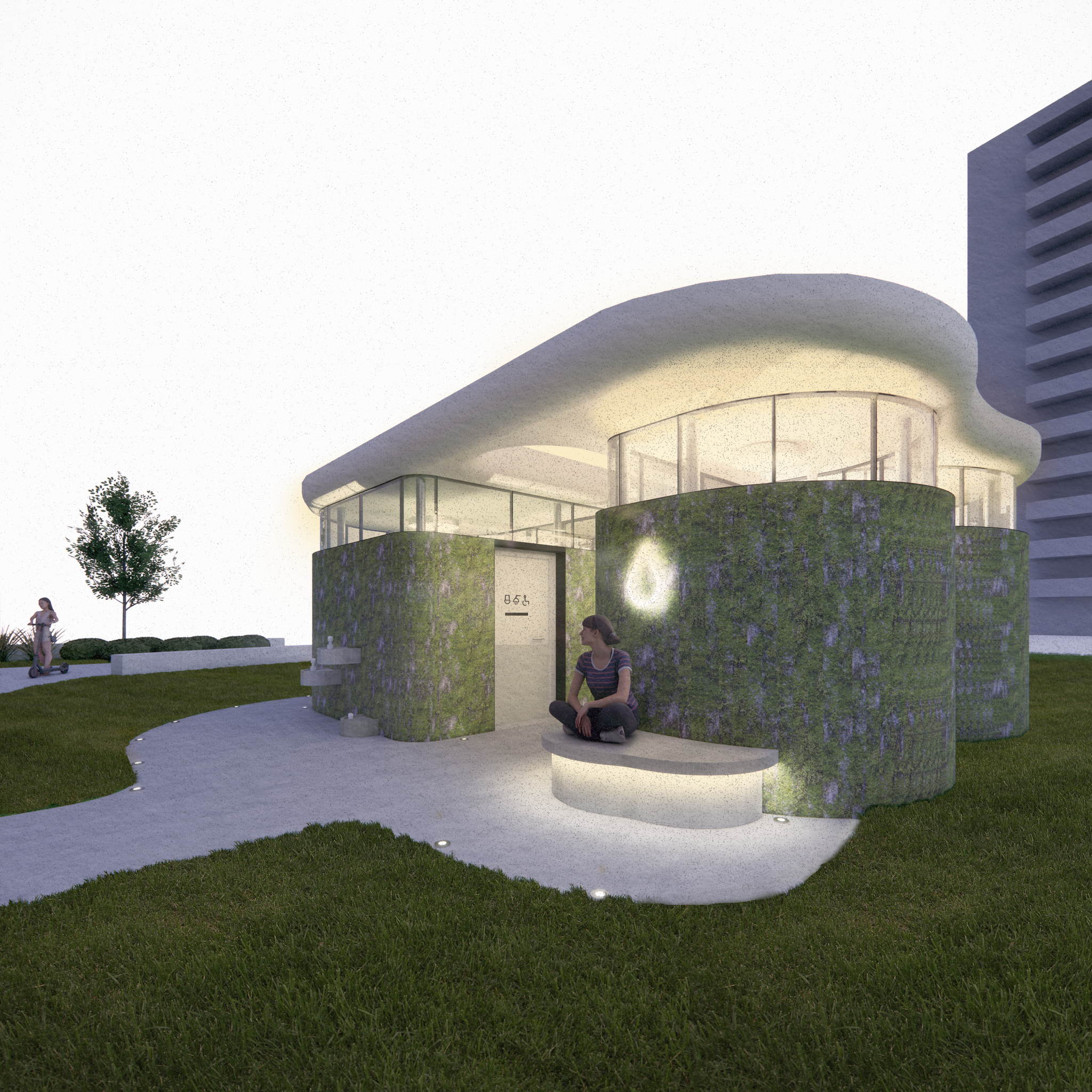

Our concept was guided by two key principles. First, we sought a flexible and scalable approach that could adapt to different sites, neighbourhoods, and contexts, allowing us to address the broader challenge of equitable, sustainable, and inclusive washrooms beyond the single park site. Second, we drew inspiration from the adaptability and interconnectedness of mushrooms. Just as mycelium creates networks that sustain neighbouring trees, our design embodies resilience, diversity, and community connectivity.

From there, we analyzed opportunities and constraints to shape modular pods informed by neurodivergent and harm-reduction design principles, resulting in their curvilinear form. Six themes then guided our detailing:

Sustainability

The green roof reduces the heat island effect, balancing the dig-out/infill process and harvesting the roof’s filtered rainwater into a grey water system for toilets. The grey water system also helps with independence from municipal services. Beyond specifying energy-conserving fixtures, solar cell glazing increases the natural light in the space and captures energy. The design also uses passive house design principles to enhance occupant comfort, reduce heating/cooling demand, and allow all-season performance. The finishes also have an environmental impact; the biodiverse concrete panels capture CO2 and improve air quality and ecological diversity. The minimal interior finishes also reduce waste.

Spatial justice

The wayfinding/signage uses a combination of pictograms and braille for easy legibility and accessibility. One of the pods even provides a shower, which can go beyond the use of allowing easy clean-up for park or beach goers, families, pets, and accidents, and provide dignified access to basic hygiene for the unhoused community.

Accessibility

Beyond the accessible signage noted above, the space provides easy access and maintenance for cleaning staff and is a universal space for families, disabled users, and caregivers. The interior finish is a water-repellent and graffiti-repellent epoxy coating, which, when combined with the central drain, allows for a complete hose-down interior. The precast interior components, like the counter, sink, and bench, have ill-defined grout lines and areas to collect grime.

Gender and culture

The pods act as independent units with full privacy for all-gender use. The space avoids stereotyping and enhances a sense of safety for women, non-binary, transgender, and other marginalized community members. Our cultural impacts also overlap with the art and community topics seen below.

Harm reduction

The pods are fitted with an emergency alarm/light system and call strips. To avoid policing and surveillance, alternative forms of safety are provided with private washrooms, clear stories illuminated, which provide an additional indication of occupancy, clear sightlines and circulation are maintained throughout the connected corridor, and naloxone access and tamper-proof sharp containers are accessible.

Role of architects and designers in shaping public policies

Architects are not only builders but also advocates for public well-being. Our role is to reframe utilitarian amenities such as public washrooms (often stigmatized as unhygienic, unsafe, or unwelcoming) into spaces of dignity, inclusion, and safety. By using our advocacy and influence to push beyond minimum code requirements, architects can help shape policies that embed universal design, harm reduction, and sustainability as non-negotiable standards. Expertise in areas like Passive House design and resilient systems makes year-round, sustainable operations feasible, while design advocacy challenges cultural stigmas that limit public washrooms to bare-minimum, seasonal solutions. In short, architects and designers are critical in influencing policy, ensuring that civic infrastructure is equitable, sustainable, and reflective of diverse community needs.

Addressing civic infrastructure gaps

Competitions like TO The Loo! demonstrate how municipalities can reimagine civic infrastructure through creativity, public engagement, and design excellence. In Canada, architectural and design competitions are already playing a transformative role in addressing civic infrastructure needs across the country, and there’s a strong case for making this approach even more mainstream. One standout example is the Calgary Central Library, where the design was selected through a national design competition in 2013. The result? A compelling public landmark blending bold form with civic purpose; praised as both iconic and highly functional. However, many municipalities can take note from more innovative and creative cities like Calgary and Toronto.

Final thoughts

Beyond any of the public benefits laid out in the description of the six major themes, well-designed public washrooms are simply a great investment for any city, leveraging public investment in the urban realm by extending the usability of parks, plazas, and waterfronts, for example. More usable and inclusive public spaces support economic vitality by encouraging tourism, festivals, and commercial activity. Thoughtfully designed, scalable public washrooms can also help to cement a city’s brand as a welcoming and equitable community.