Alberta’s first overpass beyond park borders

Neil Robson, structural engineer and project manager at DIALOG, spoke with Tanya Martins of Construction Canada about Alberta’s first wildlife overpass outside a national park. He shared key insights into the design and engineering process, provided updates on the project, and highlighted the collaboration that brought the overpass to life.

Key design challenges and how the team addressed them

The ecological challenge was to design a landscape that seamlessly extends the forest and natural terrain, guiding animals to cross safely and instinctively without encouraging them to linger.

The engineering challenge was to design two arches that each span two lanes of traffic, with the ability to expand to three lanes under each arch in the future.

Another engineering challenge was to build two large-span arches along the busy Trans-Canada Highway, which sees more than 24,000 vehicles daily, while maintaining two lanes of traffic in each direction at all times.

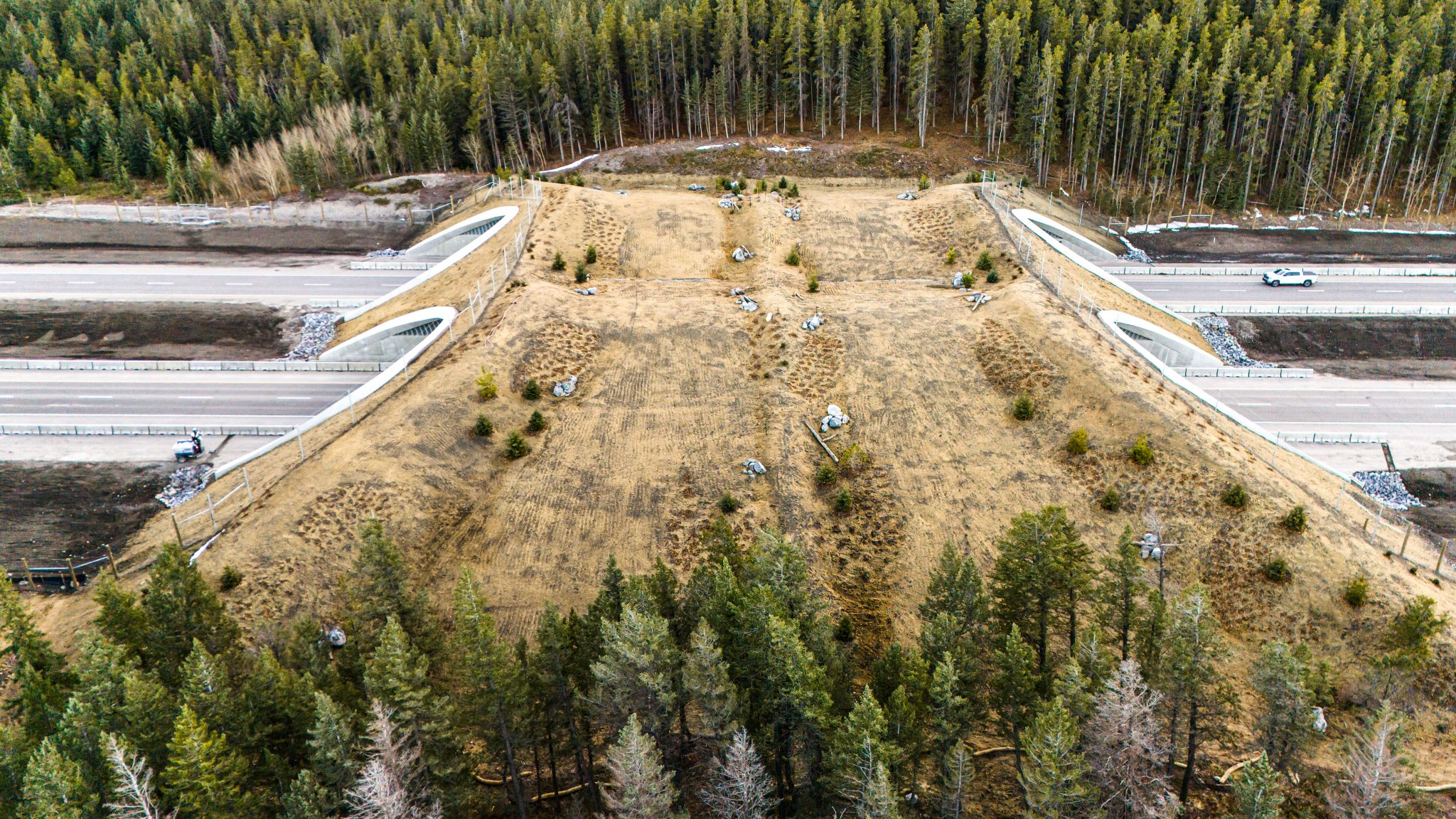

Working with the client, we selected twin 24 m (78.7 ft) steel arches, capped with soil and native plantings to blend into the forest edge.

We also installed more than 12 km (7 miles) of wildlife fencing—6 km (3.7 miles) on either side of the overpass—and added “jump‑outs” to provide a safe exit for animals that were diverted but still on the wrong side.

Role of research in the final design of the overpass

There has been decades worth of information and data collected in the area on migration paths, habitat patches, and vehicle collision data. This information was assessed to determine a crossing location that should generate the most positive impacts on collision reduction, while maintaining or improving wildlife connectivity.

The shape of the overpass and the slopes of the approaches were designed to be inviting to all species of wildlife (predators and prey). Open sightlines and the absence of blind corners help all species feel secure using the crossing.

Collaboration between Alberta Transportation and Economic Corridors, DIALOG, and environmental stakeholders

The most direct environmental stakeholder was Alberta Environment and Protected Areas, which owns the provincial park on either side of the crossing. The project team worked directly with this fellow ministry within the Government of Alberta to obtain additional land on the north side of the crossing to accommodate the sloped earth embankment. The project team also worked closely with a stakeholder to determine the alignment of wildlife fencing, striking a balance between land ownership and environmental impacts. For example, at many locations, the fencing was aligned north or south of the right-of-way delineation to minimize tree clearing or destruction of established habitat.

Footage observations

We haven’t yet made surprising observations about the larger animals using the overpass. Deer and coyotes are commonly the first to use new crossing structures. The wildlife cameras have been triggered regularly by ravens. As birds were not a focus of the design process, we do not have any background information to compare whether this is normal or abnormal.

How will lessons from the Bow Valley Gap project influence future designs?

The project serves as an example of a world-class, resilient yet elegant crossing that can be replicated in different environmental settings. The engineering team and the wildlife biologist work collaboratively from the initial location study and concept design, through preliminary design and into detailed design.

Another lesson learned is the importance of early stakeholder engagement, particularly adjacent landowners, but also utilities and environmental NGOs.

Final thoughts

Along the Trans-Canada Highway in Banff National Park, animal crossings have already helped reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions by 80 per cent.

This project is one of many innovative efforts to stitch together fragmented habitats and keep both wildlife and humans safe. Beyond its functionality, it stands as a symbol of hope.

Read more about the overpass here.