Adaptive reuse for commercial buildings

By Brian Curtner, AA, DIP., OAA, AAA, NSAA, MAA, SAA, FRAIC, Associate AIA

Inspired by innovation, tradition, and evolution, adaptive reuse is a sustainable solution for intensification that provides creative and commercial building opportunities. Canada’s building stock has undiscovered potential. By reusing buildings that might otherwise be sent to the landfill, the urban fabric is enhanced, history is preserved, and neighbourhoods are infused with new life.

By definition, adaptive reuse is the process of changing a building’s primary function and repurposing it, making what was old new again. Successful projects are born from a deep analysis of the existing building and a clear understanding of what it takes to transform older architecture into an inspired environment. Akin to the art of listening, giving new life to an old building must start by understanding its soul. Great projects start with ‘good bones’—meaning a solid structure that can be adapted and given life and intention.

Careful evaluation of existing framework can uncover unseen possibilities (and problems), unveil potential, and give the project a new program that exists in harmony with the original shell. The essence of the old is interwoven with the new, resulting in a building that is rich in culture and context.

Building sustainable communities

Conversion projects contribute to organic change in the urban fabric, focusing on previously developed areas rather then depleting the ever-shrinking inventory of greenfield sites. By building on previously developed sites, society is better able to preserve the ecological lands for habitat regeneration, food production, or pure enjoyment.

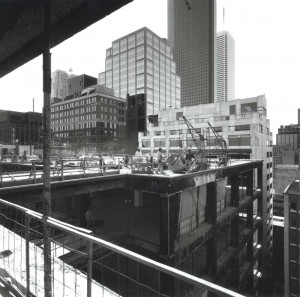

Photo © Robert Burley

Retrofitting older buildings in existing neighbourhoods creates new parameters for existing structures, supporting intensification in areas that have existing amenities, and strong transit and pedestrian access. Repurposing buildings also energizes communities and builds pride. Neighbourhoods increase in density and buildings that are loved and valued by the community are given a second chance.

“The idea is to engage the community in its own future, looking to the needs of generations to come, by creating a community that is resilient to change,” says Michelle Xuereb, sustainability strategist at Quadrangle Architects. “This can be accomplished by studying, understanding, and working in harmony with the existing infrastructure of the site.”

Smart growth of this kind maintains the integrity of the neighbourhood, making small incremental changes, resulting in holistic growth and stronger communities.

Materials, diversion, and durability

Inherently green, adaptive reuse projects avoid wholesale demolition. The 2009 LEED Canada Reference Guide for Green Building Design and Construction, developed by the Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC), indicates 12 per cent of the country’s solid waste stream in Canada comes from construction and demolition. The guide states:

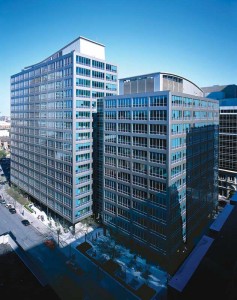

Photos © David Whitaker

Building reuse is a very effective strategy for reducing the overall environmental impact of construction. Reusing existing buildings significantly reduces the energy use associated with the demolition process as well as construction waste. Reuse strategies also reduce environmental impacts associated with raw material extraction, manufacturing, and transportation […] Reuse of existing buildings, versus building new structures is one of the most effective strategies for minimizing environmental impacts.

The sustainability of a building lies in the durability of its structure. Older facilities, assembled through traditional construction methods, are commonly built with simple materials and detailing. Traditional buildings tend to be built with natural lighting and ventilation in mind, with a low-tech passive design approach that places less reliance on mechanical and electrical solutions.

“Well-maintained buildings built with traditional building technologies have an indefinite lifespan,” said Michael McClelland, principal at ERA Architects. “They can last a very long time.”

Although a building has outgrown its purpose, it should not be seen as obsolete, but considered for the value found in its external structure, as a solid skin adaptable for another life.

Opportunities and challenges

Success in commerce and business has a direct correlation to place and location. Older structures tend to be centrally located in areas that have high visibility, transit, and general urban infrastructure. The suitability of these locations contributes to a project’s success, whether the new use is residential or commercial. Urban areas undergoing planned intensification are generally well served, preventing the need for expanding roads and utility services and contributing to higher efficiency of public works.

From the architect’s perspective, working with existing buildings can provide a wealth of opportunity. An ideal shell, older buildings are large in scale with expansive floor plates, high ceilings, and brick and beam construction. Developers have an opportunity to take advantage of architectural features and construction techniques no longer financially viable in modern building. Often, faster approvals, flexible zoning, and heritage bonusing incentives are possible due to the ‘feel-good’ aspect of retaining the urban fabric.

Not without its own set of challenges, adaptation of older architecture can be complex during planning and construction. Structural and acoustical challenges arise, environmental remediation may be required, and conflicting layouts from the existing and proposed use frequently surface. With rising energy costs, upgrades to the building envelope and mechanical systems are inevitably necessary to meet current standards. The challenge is to combine technical expertise with design excellence, maximizing ongoing energy savings while maintaining the building’s integrity.

Photo © Brenda Liu

During the feasibility stage, there are many unknowns and precise planning is difficult. Work during initial stages can be costly compared to new development. These expenses are often recovered in later stages from savings gained by reusing the original structure. The LEED Canada Reference Guide states:

Although retrofitting an existing building to accommodate new programmatic and LEED requirements can add to the complexity of design and construction—reflected in the projects soft costs—reuse of the existing components can reduce the cost of construction substantially.

Precedents and practice

A closer look at the planning, development, and construction of six successful conversions will further explore the challenges and opportunities inherent in adaptive reuse. All examples of thriving commercial success after their conversions, these projects set precedents and demonstrate the creative and commercial opportunities that adapting older buildings offer.

BMW Toronto

Quadrangle was commissioned to design a flagship showroom for BMW Toronto that was a physical embodiment of the brand. Adapting the 1970s Lever Brothers Soap Factory office building offered a unique opportunity because of flexible zoning requirements.

Photo courtesy Quadrangle Architects

Existing on a 3.6-ha (9-acre) industrial site at the junction of two major north/south and east/west downtown routes, the building was dismantled down to its structural frame and reinforced to meet modern earthquake standards. By reusing and reinforcing the existing structure, the new building was able to maintain a close relationship to the Don Valley Parkway—the north/south artery in the city’s road system. Current zoning requirements would have required the building to be set back a significant distance from the highway had the project been new construction.

Reprogrammed, the new building accommodates 5000 m2

(53,820 sf) for sales and administration over six floors, and 5000 m2 for parts and service in a new two-storey structure south of the retained building.

Incorporating a billboard into the design, and strategically glazing the building on three sides at such a close proximity to the highway, transformed the building into a physical advertisement for the brand. The showroom became a life-size display for the latest BMW offerings on the market.

State Street Financial Centre

Quadrangle’s redesign of the State Street Financial Centre, in Toronto’s business district, respects the landmark building’s 1960s-era modernist design. The building was updated to meet the needs of the 21st century while giving special consideration to the requirements of new technology firms.