PVC roofing: A case study in sustainability

The construction industry is equipped with many tools to further its mission of fostering sustainable building practices. Assessing a building’s carbon footprint is a crucial tool for addressing concerns about climate change. Embodied carbon has emerged as a critical consideration in measuring the carbon footprint of building materials. However, this is only a part of a material’s total carbon footprint. The material’s contribution to reducing operational carbon must also be considered.

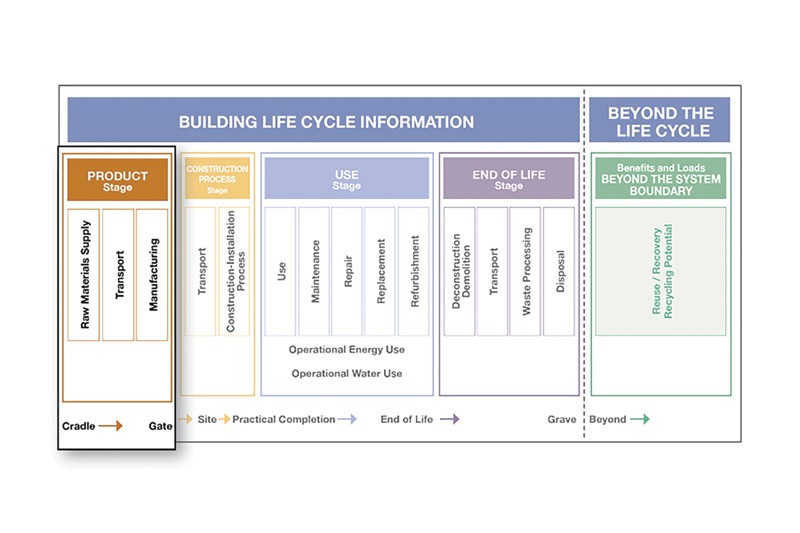

To fully understand the CO2 emissions associated with a particular material, it is necessary to consider the CO2 generated during the material’s entire life cycle, as outlined below. It is essential to understand the distinctions between cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave life-cycle calculations. Some might be surprised to hear that the more commonly used cradle-to-gate assessment only gives a partial picture of a material’s true carbon footprint. Whereas embodied carbon accounts for the CO2 emissions during only the cradle-to-gate portion of the material’s life cycle, operational carbon measures a material’s effect on reducing CO2 emissions during the operation of the building, which coincides with the use stage of a full cradle-to-grave life-cycle assessment (LCA).

Reducing the carbon footprint of construction should focus on building products that are long-lasting and resilient, can reduce CO2 emissions during the building’s operation, and are made or partially made from recycled content. A case in point is roofing. By understanding all the contributions to the total carbon footprint of various roofing material choices, construction specifiers are equipped with valuable knowledge to make informed decisions that align with carbon reduction goals while ensuring optimal roofing performance and longevity.

Here is information that can help specifiers navigate the complex landscape of sustainable building and foster a greener built environment through conscious material selection and design decision-making.

What is embodied carbon?

Embodied carbon refers to the total amount of CO2 emitted during the cradle-to-gate portion of the life-cycle of tangible goods of a particular building material. It encompasses the CO2 created from gathering raw materials, transporting them to the manufacturing site, as well as the manufacturing process itself. CO2 is generated in all manufacturing processes, including all roofing materials such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) membranes.

However, the energy used by a building after it is constructed also contributes to carbon emissions. This is called operational carbon. Taking into account embodied carbon, the material’s contribution to reducing operational carbon, and the end-of-life stage is the most accurate way to get a full picture of a building product’s complete carbon footprint.

EPDs: An incomplete picture

To manage carbon, most building and construction experts make decisions based on disclosures made through LCAs and related International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Type III ecolabels such as Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs). These documents use international standards (e.g. ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, Environmental management—Life cycle assessment—Principles and framework) developed by ISO Technical Committee 207 on environmental management. LCAs collect environmental information throughout a product’s life-cycle—from raw material extraction to its final use and ultimately to its disposal. Since these documents are often lengthy, they usually include a summary page of the results. EPDs are one such standardized summary of an LCA.

An EPD for a given material is created within boundaries described in a product category rule (PCR), as defined by ASTM. The PCR for single-ply roofing membranes, such as PVC, permits the use of information from either extraction, transport to the factory, and manufacture, referred to as a declared unit (“cradle-to-gate”), or all of that plus service life and recyclability, referred to as a functional unit (“cradle-to-grave”).

Since there is no requirement in the PCR to include the functional unit in their EPDs, many manufacturers elect to use the declared unit, the cradle-to-gate method, to derive content for their EPDs. When tools in the marketplace extract portions of the cradle-to-gate modules, it is essential for users to recognize the limitations on comparability when key product attributes, such as durability and recyclability, are not taken into account. The absence of these factors may result in fewer sustainable product selections. Purchasers should consider this when making purchasing decisions.

Most, if not all, PCRs for construction materials are based on ISO 21930:2017, Sustainability in buildings and civil engineering works—Core rules for environmental product declarations of construction products and services. For example, the PCR for single ply roofing membranes notes in section 5.5, comparability of EPDs for construction products:

- “…It shall be stated in EPDs created using this PCR that only EPDs prepared from cradle-to-grave life-cycle results…can be used to assist purchasers and users in making informed comparisons between products.”

- “EPDs based on ‘cradle-to-gate’ and ‘cradle-to-gate with options’ information modules shall not be used for comparisons. EPDs based on a declared unit shall not be used for comparisons.”

While cradle-to-gate values are accurate to a certain extent, they can also be misleading and fail to paint the full picture. Design professionals must exercise due diligence by selecting materials that are suited to the specific requirements of individual buildings and applications.

Calculations and comparisons

From the perspective of the Chemical Fabrics and Film Association’s (CFFA’s) vinyl roofing division, there are shortcomings with the way carbon data is reported. To date, these calculators have been limited to what are referred to as the A1-A3 impacts (i.e. cradle-to-gate) for a single product purchase; therefore, they should not be used for direct comparisons of products. What these calculations do not consider are the longevity of the finished product, the embodied carbon that would result from multiple installations with an overall building’s service life, as well as its contributions to reductions in energy and waste consumption over decades.

This paints an inaccurate picture of the overall CO2 emissions associated with a product such as PVC roofing because factors such as the “use” and “end-of-life” stages are not being considered. Further, CO2 emissions are either reduced or never generated when using PVC roofing as a building material, as these roofs significantly reduce a building’s energy consumption.1 These results outweigh and offset any CO2 emitted during its creation.

The energy-saving benefits of PVC roofing are well-documented. It is a product that deserves a more accurate method of conveying embodied carbon to end-users. Therefore, a more accurate way to measure embodied carbon is through cradle-to-grave calculations, which account for the entire product life-cycle. This provides a more comprehensive measurement of a product’s environmental impact.

Reducing the carbon footprint of construction

Limiting carbon in construction focuses on building products that are long-lasting and resilient, can reduce operational carbon emissions, and are made or partially made from recycled content. PVC roofing checks all three boxes. PVC roofing that has reached the end of its use phase is recyclable and can be repurposed into new roofing material or other vinyl-based products.

Post-consumer recycling of PVC roofing began in the U.S. in 1999, and the industry continues to make strides in increasing the recycled content in its products. Currently, roughly 453,592 kg (1 million lb) are recycled each year at the end of a PVC roof’s life. Estimates indicate that approximately 8 million kg (19 million lb) of PVC roofing membranes are currently available for recycling, based on historical volumes of installed roofs and the average lifespan of the material. The CFFA’s goal is to increase the number of PVC roof membrane recovery projects annually, resulting in a greater amount of material being diverted from landfills.

Beyond embodied carbon

Embodied carbon is merely one attribute to consider in the product evaluation process. For roofing, informed decisions on product specifications should be made in the context of the application. Using a multi-attribute approach and considering aspects such as performance, durability, and reference service life (RSL) provides a more comprehensive measure of a product’s sustainability and impact.

The longer a roof lasts—and the more resilient it is in standing up to weather, fire, and other environmental conditions—the longer it stays out of landfills and the less likely it will need to be replaced with new materials. This durability and longevity of PVC roofing material contribute greatly to its reputation as a green building material choice.

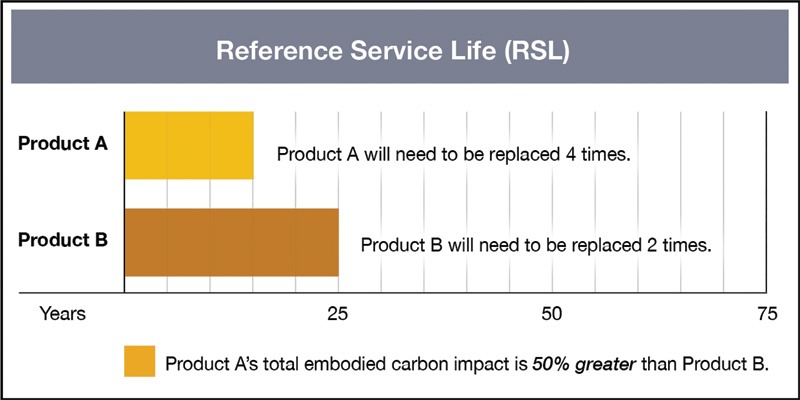

Many building envelope systems will be replaced several times throughout the baseline RSL of 75 years for long-life buildings. The RSL of such systems and products is often the largest driver of their embodied carbon impact over the life of the building. For example, if product A has an RSL of 15 years and product B has an RSL of 25 years, the products will be replaced four and two times, respectively, after the original installation.

Even if product A’s embodied carbon is 10 per cent less than product B’s, during the building’s RSL, product A’s total embodied carbon impact will be 50 per cent greater than product B’s because product A needs to be replaced more often. Even with a 15 per cent differential, product A’s total impact will be 41 per cent greater than product B’s over the building’s RSL.

This example illustrates the importance of considering multiple performance attributes when selecting materials. Since reliance on a cradle-to-gate method for embodied carbon may lead to unintended consequences, considering more than one metric in assessing a material’s carbon impact, such as its RSL and replacement cycles, provides a truer estimate of the product’s impacts over the life of a building.

Notes

1 See.

Author

Bill Bellico is vice-president, marketing and inside sales, Sika Corporation. Bellico has worked in the commercial construction industry for 20 years in Sika’s roofing and flooring divisions. He began his career in sales and evolved into roles in sales and marketing management, as well as leading digital transformation projects for the company. He is a LEED-accredited professional with a strong background in sustainability. Bellico is the current acting marketing chair for the Chemical Fabrics & Film Association (CFFA)—vinyl roofing division, as well as the Vinyl Sustainability Council, and is also a participating member of the Roofing Technology Think Tank (RT3). He has bachelor’s degrees in English and psychology from the Bridgewater State University and completed the business strategy certificate program from Cornell University.