The sound of wellness: Flooring that lasts

As occupant health and wellness remain vitally important aspects of the built environment, acoustics have emerged as a key factor in creating spaces that foster productivity, rest and positive experiences. Whether in health-care facilities, offices, hotels, multifamily residences, educational institutions or fitness centres, managing noise is essential to supporting both mental and physical well-being. One often overlooked element in the acoustic equation is flooring—a material choice that directly influences impact noise from footsteps, dropped objects, rolling carts, and even weight drops in gyms. The right flooring solution can play a transformative role in reducing noise levels and enhancing overall occupant satisfaction.

The challenge of noise across building types

Noise can be a disruptive factor in nearly every type of building. In health-care settings, elevated and unexpected sounds can affect patient recovery by disrupting sleep, increasing the need for medication, and ultimately extending hospital stays. For staff such as nurses, excessive noise can lower speech intelligibility, impair decision-making, and contribute to fatigue.1

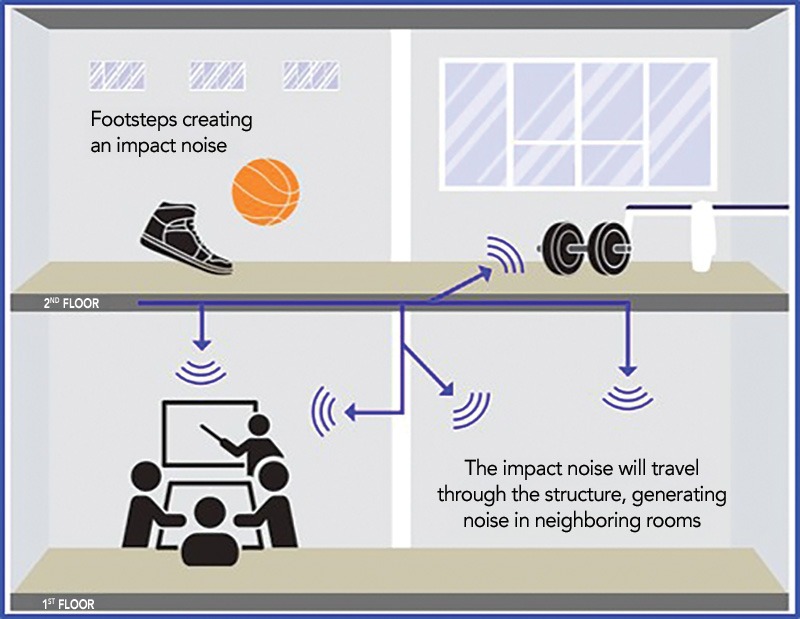

In commercial office environments, background noise from footsteps, conversations, and moving furniture can reduce concentration and productivity. Hotels and multifamily residences face challenges maintaining restful spaces for guests and residents, especially when gyms, conference areas, or restaurants are located near sleeping areas.2

Educational settings require low noise levels for optimal learning, while fitness facilities must manage impact noise from heavy weights, cardio machines, and high-intensity workouts.

Managing impact energy to reduce noise

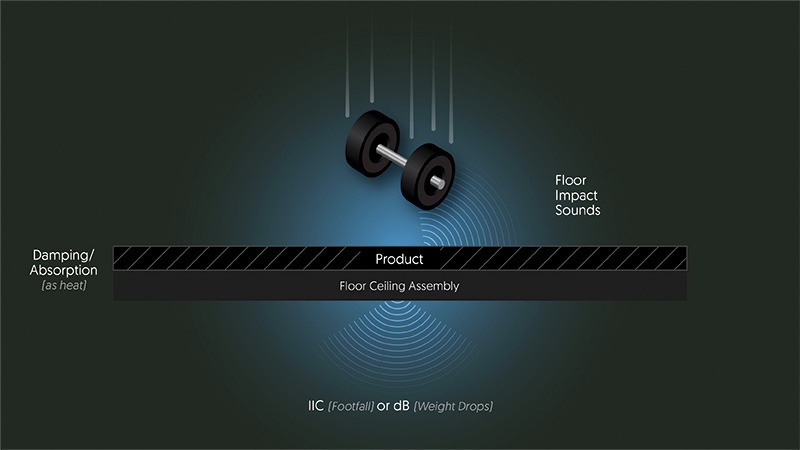

When an object—whether it is a shoe, a chair leg, or a dropped weight—makes contact with the floor, the object’s kinetic energy is redirected. That energy is distributed in several ways: some is returned to the object (bounce), some is transformed by the floor (heat), and some is transmitted as noise into the same room or adjacent spaces. Because the relative amounts of heat and transmitted noise are proportional to the mass and damping of the floor-ceiling assembly, the building materials therein are of critical importance.3 In other words, the floor can help manage how and where the energy goes.

In acoustical engineering, this transmission is often measured through metrics such as Impact Insulation Class (IIC) and High-frequency Impact Insulation Class (HIIC). IIC quantifies how well a floor-ceiling system attenuates low-frequency impact sounds—such as footsteps or dropped objects—while HIIC is more sensitive to high-frequency sounds, such as the sharp click of high heels. Both ratings are influenced by factors such as surface hardness, underlayment composition, and structural mass. For example, denser materials may reduce low-frequency “thuds” but allow higher-frequency sounds to pass through, whereas resilient underlayments can absorb and dissipate energy across a broader spectrum.

Historically, carpet was widely used in many building types because of its comfort and because its soft surface naturally reduces impact noise. However, modern design trends favour hard-surface flooring for light and temperature management, esthetics, durability, and maintenance, and these surfaces readily transmit impact noise. This is especially problematic in mixed-use and multistorey buildings where noise can travel between floors, via walls, and from tenant to tenant. By carefully selecting and combining flooring materials, designers can fine-tune acoustic performance to create environments better suited to health-care, educational, residential and commercial needs.

Flooring as a key acoustical solution

Performance flooring can significantly reduce sound from impacts and interactions with the floor, such as footfall, dropped objects, dragging furniture, or rolling carts. The effect can be orders of magnitude in terms of perceived noise. In hospitals, quieter flooring materials can reduce rolling and impact noise levels enough to encourage lower speaking volumes—a reverse of the ‘cocktail party effect,’ where everyone raises their voice to be heard. In fitness settings, specialized rubber flooring absorbs and isolates impact noise from dropped weights or fast-paced workouts, protecting noise-sensitive areas like offices, hotel rooms, or classrooms located nearby.

Evidence-based design and acoustical performance

Evidence-based design (EBD) is more than a philosophy—it is a disciplined approach that draws on scientific research and data to influence the built environment in ways that positively affect human health, behaviour, and experience. EBD considers numerous factors, including visibility, circulation paths, ergonomics, and acoustics. It is especially relevant in facilities like hospitals, schools, and workplaces, where design decisions have measurable outcomes.

Environments inundated with unnecessary or uncontrolled noise can cause stress, hinder sleep and healing, and decrease concentration or productivity. The ability to proactively address acoustical issues rather than retrofit solutions after problems arise is a hallmark of thoughtful, occupant-centred design.

In multi-family housing, building codes require a minimum Impact Insulation Class (IIC) rating of 50 to reduce impact sound transmission between residential units. This minimum contributes to a baseline of acoustic comfort and privacy. Similar guidelines exist across other sectors, including hospitality, education, and health-care.

Studies comparing hard-surface materials, such as vinyl composition tile (VCT) and luxury vinyl tile (LVT), with acoustically engineered flooring systems have shown significant differences in both decibel levels and IIC ratings, which measure how well a floor assembly reduces impact sound transmission.4 As mentioned, in health-care settings, quieter flooring can support healing by enabling rest and reducing stress on both patients and staff.5 And in hospitality or multifamily buildings, it contributes to a more peaceful, premium experience for occupants.6

Building codes in multi-family housing require a minimum Impact Insulation Class (IIC) rating of 50 to reduce impact sound transmission between residential units. This minimum contributes to a baseline of acoustic comfort and privacy. Similar guidelines exist across other sectors, including hospitality, education, and health-care.

Well-designed flooring aligns with EBD principles to meet and exceed minimum requirements. For example, a 3 mm (0.12 in.) LVT on a 152-mm (6-in.) concrete slab structural floor might typically achieve IIC 40 or less, whereas an LVT with a rubber underlayment might typically achieve IIC 50 or more, and a vinyl plank with an integral rubber pad might typically achieve IIC 54.

Ultimately, EBD encourages architects, designers, and facility planners to assess the long-term impact of their decisions. Flooring that contributes to reduced noise transmission is a strategic investment in the health, satisfaction and productivity of every person who walks through the space.

Real-world applications and testing

Engineered floorings sometimes include dissimilar materials factory-laminated to achieve otherwise impossible performance. Such technology can enhance force reduction and energy restitution characteristics and change the way sound is generated and transmitted in order to help control both in-room and transmitted impact noise.

Independent testing has shown that some proprietary surfaces can achieve a notable reduction in perceived loudness compared to common hard-surface materials. For example, common VCT and LVT can generate an increase of well more than 100 per cent in perceived in-room loudness relative to certain factory-laminated floor surfaces.7

Designing for acoustics in any building type

Selecting the right flooring for a space requires balancing multiple priorities: esthetics, durability, maintenance, hygiene, comfort and acoustics. In hospitals, this might mean choosing a surface that can withstand frequent cleaning while reducing noise from rolling equipment. In hotels, it might mean using sound-reducing flooring in hallways above guest rooms. In educational facilities, it could mean specifying impact-reducing materials in multipurpose rooms or gymnasiums to protect classrooms nearby.

Ultimately, good design is a balance of the project’s many performance goals. Flooring is one of the few elements that directly affects impact noise in the room itself, transmitted noise to surrounding spaces, maintenance, and more—making it a critical piece of the acoustical design puzzle.

Conclusion

As the demand grows for healthier, more comfortable, and more productive indoor environments, acoustics continue to play

a defining role in the built environment. From hospitals to hotels, offices to fitness centres, flooring choices can make a measurable difference in reducing noise, supporting wellness, and improving the overall experience for

every occupant.

By incorporating evidence-based design principles and selecting materials engineered for acoustical performance, designers and facility managers create spaces that sound and feel better.

Notes

1 See.

2 Refer.

3 Read “Structureborne Sound Isolation” in Handbook of Acoustical Measurements and Noise Control.

4 Visit.

5 Learn more.

6 Refer.

7 See.

Author

Justin Reidling is an acoustic engineer at Ecore, bringing years of multifaceted experience as a product engineer and acoustical consultant. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering with a minor in acoustics from Kettering University in Flint, Michigan.