Beyond retail: Rethinking the future of Hudson’s Bay stores

With Hudson’s Bay having officially closed all its stores nationwide, hundreds of thousands of square feet of prime retail real estate now sit vacant, creating ripple effects for landlords, local economies, and the communities these malls once anchored.

At WZMH Architects, the retail design team has been exploring a question many developers and city leaders are now confronting: What comes next for Canada’s anchor stores?

Supreet Barhay, principal and head of retail at WZMH Architects, spoke to Tanya Martins, online editor at Construction Canada, on what’s next.

What makes a successful “next life” for a mall anchor?

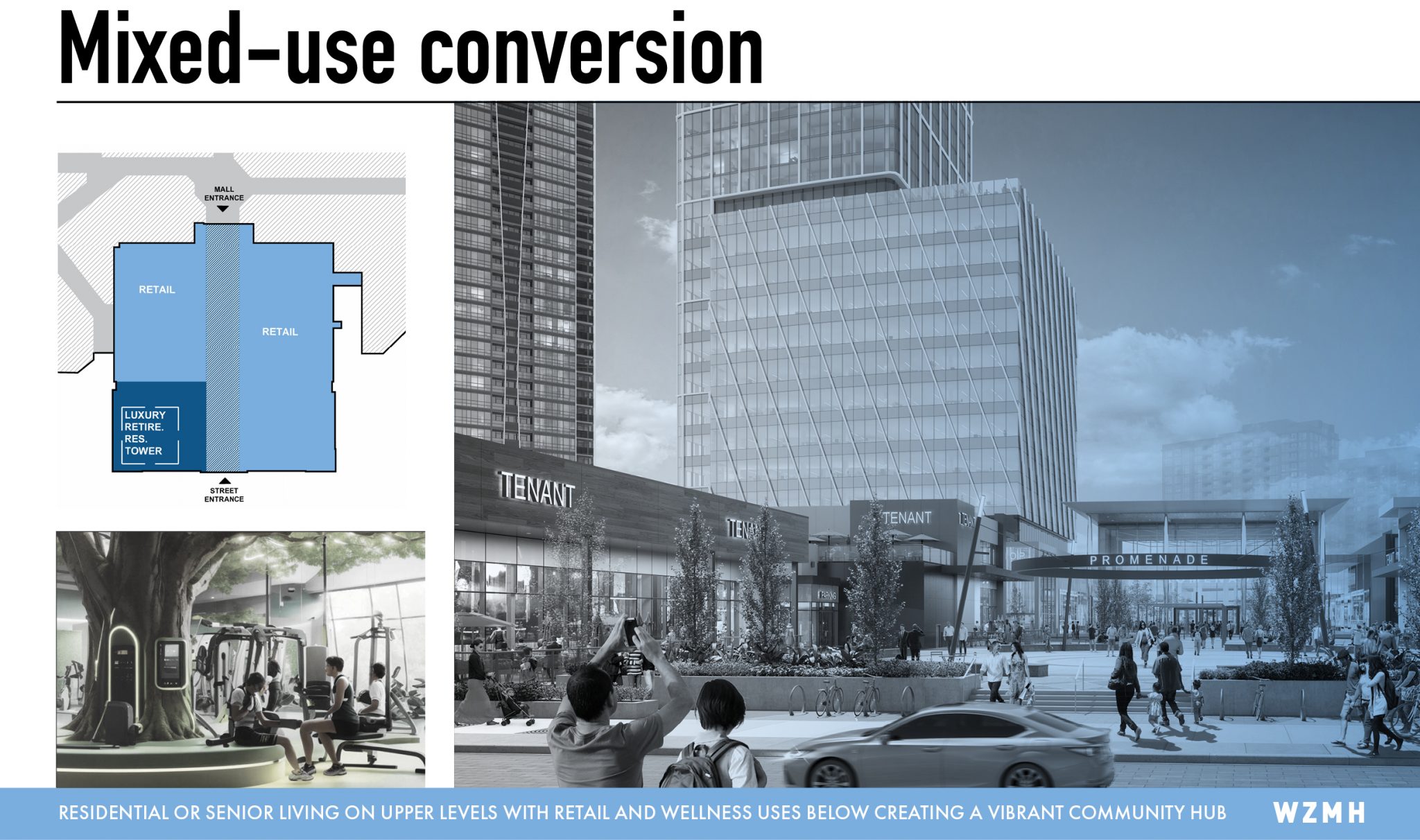

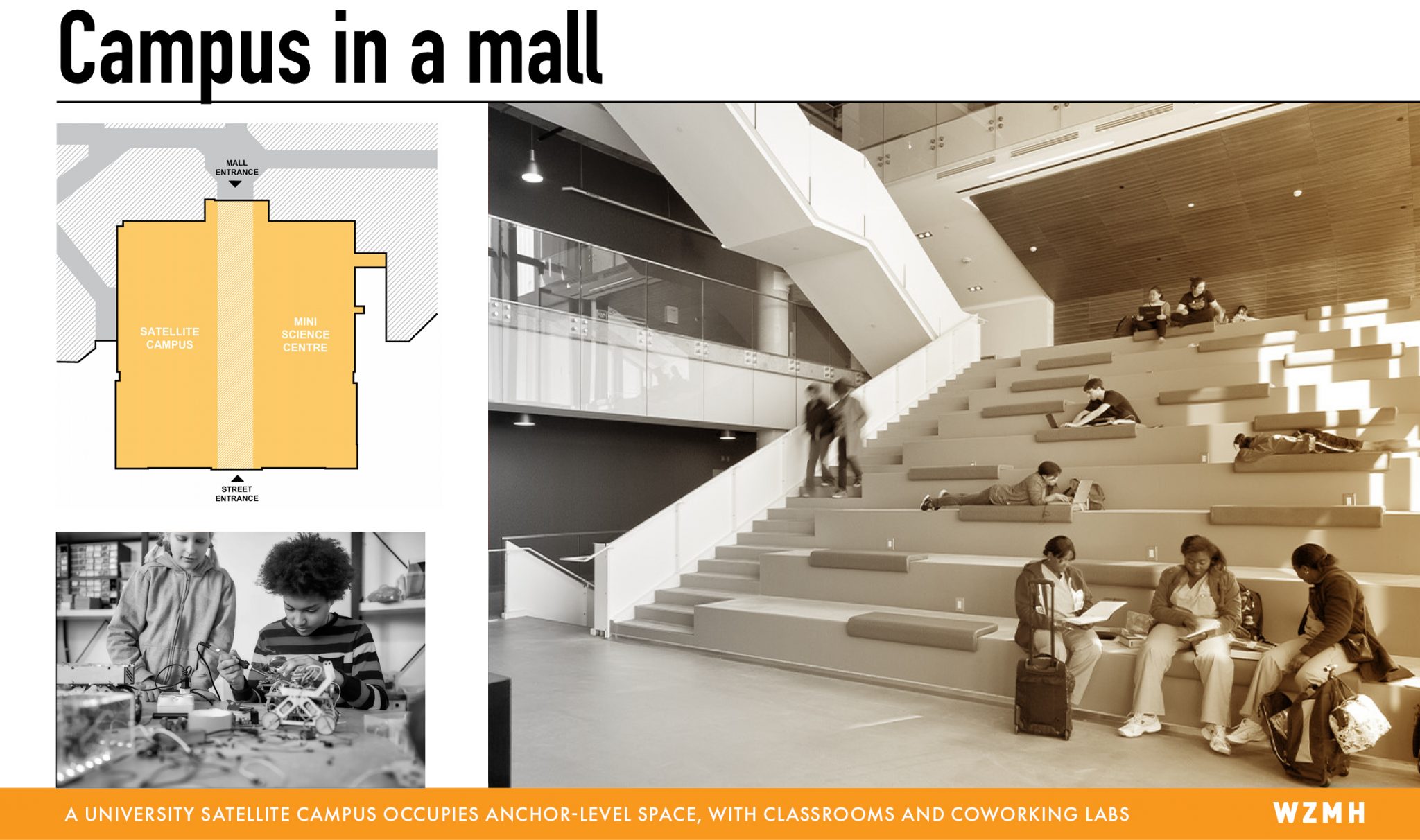

Through recent concept work exploring the future of former Hudson’s Bay stores across Canada, WZMH has seen how large-format anchors can be repositioned as long-term community and economic assets rather than short-term retail fixes. From a design perspective, the most effective adaptive reuse projects are flexible, multi-use, and deeply rooted in context. They reconnect former anchors to mall circulation, introduce transparency and permeability where possible, and extend activity beyond traditional retail hours.

How does adaptive reuse change mall-scale urban design?

Adaptive reuse fundamentally shifts malls from single-purpose retail environments into mixed-use districts. At the mall scale, this requires rethinking circulation patterns, access points, servicing zones, and public interfaces.

Former anchors can become secondary centres within a site, supporting education, healthcare, residential, employment, or cultural uses. This diversification distributes foot traffic more evenly, reduces reliance on peak retail hours, and introduces new user groups, such as students, seniors, workers, and patients, who activate the site throughout the day.

These transformations often reveal opportunities to introduce new public entrances, civic-facing programs, and stronger physical and visual connections to surrounding neighbourhoods. As a result, adaptive reuse helps malls function more like integrated urban campuses than enclosed retail destinations.

Why do traditional retail backfills struggle at the anchor scale?

Traditional retail backfills can be challenging at the anchor scale, largely because these spaces were originally designed for a specific department-store format rather than today’s more diverse retail models. Their large floorplates, deep interiors, limited access to daylight, and substantial servicing infrastructure can exceed the needs of many contemporary retailers.

When backfilled by a compelling, well-capitalized retailer with a strong destination or experiential offer, retail can perform well and meaningfully contribute to mall revitalization. However, simply replacing one department store with another conventional retail concept can recreate exposure to shifting consumer behaviour unless the tenant has the scale, brand strength, and long-term commitment to fully own the space. Retail-only backfills also tend to be more sensitive to market cycles, seasonal demand, and e-commerce pressures, which can affect long-term stability.

The scale of vacancy created by Hudson’s Bay closures has highlighted that replicating the traditional department-store model alone rarely addresses the broader structural and economic realities facing today’s malls.

How do existing HVAC, electrical capacity, and vertical distribution systems constrain or enable conversions to energy-intensive programs, and when does replacement become more economical?

Former anchor stores often benefit from robust structural capacity and generous ceiling heights, which are significant advantages for reuse. However, HVAC and electrical systems were typically designed for retail loads and may not meet the demands of energy-intensive programs such as STEM labs, wellness campuses, or senior living.

In some cases, systems can be selectively upgraded or re-zoned to support new uses. In others, full replacement becomes more economical when lifecycle costs, operational efficiency, and long-term flexibility are considered. Vertical distribution including stairs, elevators, and shafts, can be both a constraint and an opportunity, particularly when introducing multi-level or mixed-use programs.

Early technical assessments are essential to determine whether retrofit or replacement delivers the best value, especially when sustainability, carbon reduction, and future adaptability are priorities.

Can these buildings become civic spaces again? What design strategies help former department stores feel more like public destinations?

Yes, former anchors can absolutely become civic spaces again. Doing so requires a shift from inward-facing retail design toward openness, visibility, and social engagement.

Key strategies include introducing daylight through new openings or atriums, creating public-facing entrances and gathering spaces, and layering uses that encourage repeat visits. Integrating cultural programming, education, healthcare, or food destinations helps reposition the anchor as a place of care, learning, and connection rather than consumption alone.

Materiality, acoustics, and intuitive wayfinding also play an important role in making large-scale spaces feel human, welcoming, and legible. The goal is to transform vacant retail boxes into places with identity, purpose, and shared value.

Adaptive reuse is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Each anchor must be evaluated within its specific urban, structural, and community context.

As retail continues to evolve, the future of malls will be defined less by what they sell and more by how they serve their communities. Thoughtful adaptive reuse allows these large-scale structures to remain relevant, resilient, and productive for decades to come.